THE PYRAMIDS.

THERE were at one time over seventy pyramids in the valley of the Nile; but many of these are entirely destroyed, and others partly torn down.

The largest and most noted of them are on the western bank of the Nile, opposite the old city of Cairo, and about eight miles from it. These stand a short distance back from the river, and tower grandly above the level plain. It seems to be true that, as one traveler remarks, "the grandest architectural achievements of man are usually found in level countries,

where they can display their vastness and majesty without fear of rivalry from the mightier works of God."

The approach to the pyramids, by one traveling westward from Cairo and the banks of the Nile, is at first a rich green plain, and then the desert.

They are at the beginning of the desert, on a ridge that lifts them above the valley of the Nile.

Dean Stanley says: "It is impossible not to feel a thrill as one finds one's self drawing nearer to the greatest and most ancient monuments in the world, to see them coming out stone by stone into view, and the dark head of the Sphinx peering over the lower sand-hills. Yet the usual accounts are correct, which represent this nearer sight as not impressive; their size diminishes, and the clearness with which you see their several stones strips them of their awful and mysterious character. It is not till you are close under the Great Pyramid, and look up at the huge blocks rising above you into the sky, that the consciousness is forced upon you that this is the nearest approach to a mountain that the art of man has produced."

In the picture is a good representation of the three largest ones near Cairo. They stand perfectly square, with the sides facing the cardinal points, and the entrance is toward the north. Judging from the accuracy with which these monuments are placed, the ancient Egyptians must have had some knowledge of astronomy. These were in all probability built by the earliest Egyptian kings.

The largest of them is known as Cheops, the second as Chephren, and the third, which is made of choicer materials than the others, as Mycerinus; and from inscriptions found on them, it is thought that these pyramids were built by the kings whose names they bear.

The Sphinx is a large idol built close by the

Great Pyramid. It has the head of a man, with the body and paws of a lion. It is cut out of solid rock. The face is mutilated, and the nose gone. It was worshiped as a god, and between its paws was an altar for offerings.

The pyramids are all constructed on the same plan, and so a description of the largest will answer for them all. It covers nearly thirteen acres, and stands on a base of native rock, which raises it above the inundation of the Nile. It is built of layers of huge rocks, rising one above another in the form of steps. The stones of the Great Pyramid vary from four and one-half feet to two feet in thickness, with a breadth of six and one-half feet. The steps were filled with blocks of stone, and the whole was covered with a smooth coating of casing-stones.

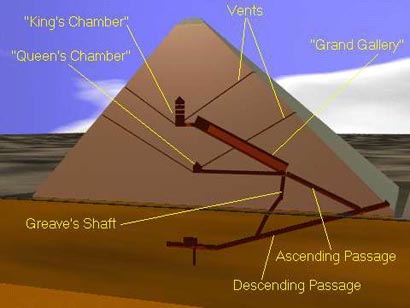

Inside the pyramid are three chambers,—one in the foundation rock; one farther up, in the masonry, known as the " Queen's Chamber," which is lined with polished stone; and another, near the center, called the "King's Chamber," lined with polished granite. In this chamber has been found a sarcophagus, or stone coffin.

It is said that the Great Pyramid was thirty years in building; the first ten years were taken up in constructing a causeway for bringing from the quarries in the southern part of Egypt the huge masses of rock used, and the remaining twenty years were taken up in building the vast monument. An ancient historian says that there were one hundred thousand men employed at the same time on the work, and at the end of three months their places were supplied by another gang. On these monuments are inscriptions telling of the amount of onions, radishes, and garlic doled out to these workingmen. They were compelled to work very hard, in bondage not less bitter than that of the Israelites.

Some of these monuments were built two or three thousand years before Christ. Perhaps Abraham passed them when he went down into Egypt in the time of famine; Joseph may have been familiar with them; and later still, Moses or the children of Israel may have beheld them daily; and their hard bondage in mortar and brick may have resulted in the erection of some of these monuments; for several of the smaller ones are built of brick, and covered with stone.

There are many conjectures as to the purposes for which these monuments were built. They were probably intended for the tombs of the royal families. In some of them have been found sarcophagi, or stone coffins, inside of which were placed the wooden coffins with the embalmed bodies of the dead. As soon as the king ascended his throne, he began to build his monument and his tomb. The work was carried on through his life, and at death his body was embalmed, and placed in the stone coffin in the chamber of the tomb.

The pyramid was then topped off, and the narrow passageway leading to the chamber closed. Why so much labor should be put upon one tomb may perhaps be accounted for from their religious belief. The Egyptians thought that at death the soul of the person would pass into the body of some animal born at that moment, and from that would pass through the bodies of all the animals, when it would again pass into the human frame and be born anew. The time, which was allotted to this process, was three thousand years. So they took great care to preserve the body, and placed it in rock-hewn tombs that it might be ready, after the flight of three thousand years, to receive the soul.

The present inhabitants of Egypt have little respect for the embalmed bodies of their ancestors, for they use these mummies for fire-wood. This but furnishes another example of the unchangeableness of the Divine sentence, "Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return." In the words of one of England's early poets,

"In vain do earthly princes, then, in vain

Seek with pyramids, to heaven aspired,

Or huge colosses, built with costly pain,

Or brazen pillars, never to be fired,

Or shrines, made of the metal most desired,

To make their memories forever live:

For how can mortal immortality give?"

W. E. L.