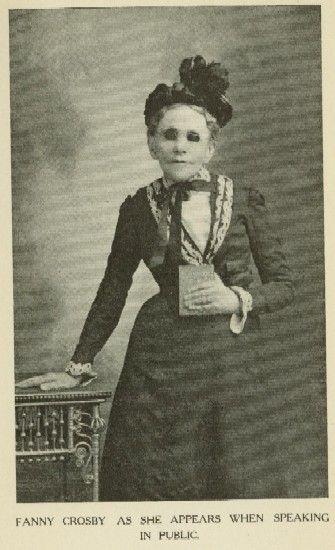

FANNY J. CROSBY.

THERE are so many girls and boys that like to find the name of Fanny J. Crosby at the head of the songs they sing, that perhaps they would like to hear a true story about this lady. Some of you may not know that she is blind, and has been ever since she was a very small child. For all that, she is one of the happiest women you can know.

She says that when she was a little girl, it suddenly came to her mind that she was not like other children, and must always live in a dark world of her own; but she made up her mind then and there not to be unhappy about it, but to take all the good she could get, and give as much to others as possible. And so she has.

Well, last winter she was invited to speak in one of the industrial schools of New York City.

About two hundred children, who came from the poorest and most destitute of homes, were gathered in the schoolroom at Cottage Place that afternoon to hear the "blind lady," and quite a number of ladies and gentlemen were on the platform.

First the children sang very heartily and sweetly several songs, and spoke several "pieces," and then Miss Crosby gave them one of her own "stories in verse," in which she imitated the various street-calls so naturally that the children shouted with laughter. Then they had different exercises, free gymnastics and "kitchen-garden" songs, until Miss Crosby told them it was time for a sober story, and she began by saying—how that more than fifty years before, a little baby girl was born up in Connecticut, who seemed very bright at first, but when she was about six weeks old, a great misfortune happened to her, and she lost her sight.

"That was just like myself," Miss Crosby said, and the children smiled. Then she told how the baby girl grew, and what nice times she used to have sliding down hill in the winter, and playing in summer with her mates, who were always very kind to her. But when this blind girl was eight years old, she was sent to New York to learn to read in the Institute for such afflicted ones. She cried at leaving her mother, but she wanted to go, so as to know something like other girls. There she grew up, and finally became a teacher in the Institute, and had always remained in the city; but though she had been blind, she believed she had had as many happy hours as many who could see, for she trusted God that he knew what was best for his child.

When Miss Crosby sat down, a gentleman who had been quietly listening to the story, stepped forward and said he had a story to tell. He said that nearly fifty years ago, he, too, had lived up in the State of Connecticut, and among his child friends and playmates had been one little girl who, strange to say, had been just as the lady had told, entirely blind; but he said he always liked to draw her about, she was so happy and cheery, and never allowed any quarreling or disputing. Then he said, "very strange," but that little girl, too, came to New York into the same Institute the lady had mentioned, and he did not see her again for thirty years. Then he visited the Institute, and saw his little playmate grown into a busy, happy woman, and spent a very pleasant hour with her, talking over old times and friends. And again, he said, years went by, and he had never met his friend since until—and there he stopped.

Miss Crosby was sitting leaning toward the speaker, her face shining with emotion and hands trembling with eagerness.

"Children," said the Principal, stepping forward, "who were this little girl and boy'?"

"This lady and gentleman!" shouted the quick-sighted children.

And then the gentleman came up to Miss Crosby. "It's George K., isn't.

I knew the voice," she said, while they stood shaking hands very heartily, and the children clapped their hands in joyful sympathy, and the older people waved their handkerchiefs, and tried to cough to hide their tears.

When all was quiet again, Miss Crosby recited one very sweet poem she had written for New Year's, the children sung their "Holy, holy, holy," and went away, leaving the blind author and her old-time friend to have a quiet little chat of the way in which God had led them.

But these poor children had learned one new lesson from Miss Crosby,—that a person does not need to live an unhappy or useless life, even if God has sent some great and sad misfortune into it,—and the next time any of you sing that sweet song:—

"All the way my Saviour leads me;

What have I to ask beside?"

remember that it is not only the song of the author's pen, but of all her bright, helpful life as well.

—Howe Benning