RULING CIRCUMSTANCES.

IT is a false philosophy, which teaches that circumstances make or mar men. A failure 'may ruin one man, and cause another man to succeed.

The men, not the failure, determine the difference in the results. Cyrus W. Field, 'through whose enterprise the Old World was cabled to the New, was overthrown by a disastrous failure a few years after he began business as the junior partner of a paper firm. Young Field fell to rise again.

And in promising with his creditors, he opened a paper commission house in the city of New York. He began with a small capital and little credit, but with industry, promptness, and the determination to sell paper. He was 'up early and late.

The doors and windows of his store were the first opened in the morning and the last closed at night.

His salesman, bookkeeper, cashier, and porter were always at their post of duty, for he was all four. Customers were impressed with his precise habits and the methodical way in which he managed his business. He had a place for everything and a time for every duty. At noon, no matter who was present, out came the tin pail in which he had brought his dinner, a napkin was spread on the desk, and a "cold bite" eaten.

Within ten years, the industrious young man had built up a large business, and paid off his creditors, principal and interest. Then he became possessed by the grand idea of connecting Europe and America by an Atlantic telegraph. Men laughed at him as visionary; obstacle upon obstacle interposed; failure followed upon failure. Yet he held to his great thought, and made the two worlds neighbors. Did circumstances make him, or did he make circumstances do his bidding?

Selected.

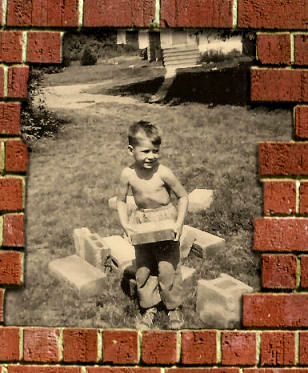

THE BOY AND THE BRICKS.

A BOY, hearing his father say 't was "a poor rule that wouldn't work both ways," said

"If father applies this rule to his work, I will test it in my play."

So setting up a row of bricks three or four inches apart, he tipped over the first, which, striking the second, caused it to fall on the third, and so on, through the whole course, until all the bricks lay prostrate.

"Well," said the boy, "each brick has knocked down his neighbor which stood next to him; I only tipped one. Now I will raise one, and see if he will raise his neighbor. I will see if raising one, will raise all the rest." But he looked in vain to see them rise.

"There, father," said the boy, "is a poor rule; 't will not work both ways. They knock each other down, but will not raise each other up."

"My son," said the father, "bricks and mankind are alike made of clay, active in knocking each other down, but not disposed to help each other up. When men fall, they love company; but when they rise, they love to stand alone, and see others prostrate below them."