BY-AND-BY.

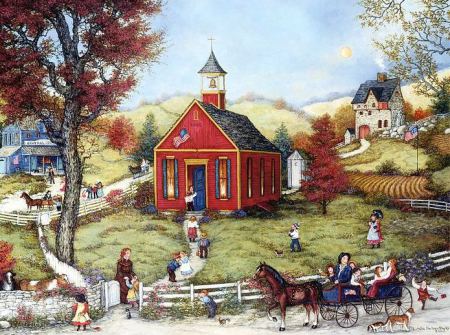

HALF a dozen boys and girls were sitting in front of a country schoolhouse, during the noon intermission. They had eaten their luncheon, and while waiting for the teacher to come, were talking, half soberly, half in fun, of what they would do when they grew up.

"I am going to be rich," said Will. "I shall go to work pretty soon, and save every cent I can get. Grandfather says, ' A penny saved is worth two earned."

"When are you going to begin saving!" asked Madge, who remembered that her brother could hardly keep a cent even one day, for it almost burned a hole through his pocket, till it found its way to the confectioner's or the toy-shop.

"Oh, by-and-by," replied Will; "I don't have enough now to pay for saving."

"And-I," said Ned, who was set down as the most indolent fellow in school, "I am going to make an author. It will take work and study; but when I get older, I am going to bend right down to the work, and I will astonish you yet by my knowledge."

"You will have to begin pretty soon," Madge threw in again, "if you ever make a scholar."

"Oh, there's time enough by-and-by. Men work, boys play; "and Ned rolled over on the grass, stretched his feet into the sunshine, perfectly resigned to be a great scholar some day.

Jo was always getting into trouble. This morning he had been in dire disgrace for chalking a picture on Will's back. During the talk he had sat very quietly, and now when Madge tapped him on the shoulder, and said, "A penny for your thoughts, Jo.” He looked up very earnestly, and said,—

"I tell you, boys, I'm going to be good when I get to be a man. I am going to make other folks happy, and always be good."

"That's right," said Madge. "Now I suppose there will be no more chalk pictures and broken rules in school. How glad the teacher will be!"

"Oh, ho," cried Jo, "I didn't say now, but when I get to be a man. One mustn't try to tie up boys. Let 'us have our good times. Chance enough to be steady by-and-by."

"As the twig is bent, the tree's inclined," said Madge. "Now you boys all think you are going to do something wonderful when you grow up.

I believe you will do just as you do now. You will never get to the by-and-by where Will, will save his money, Ned study, and Jo be good, unless you commence right off."

Just then the school bell rang, but after all was in order, the teacher, who had overheard the conversation, tapped on her desk, and said:—

"I heard you, just now, telling of what you would do in the future. That is all right. Your parents are giving you- the advantages of this school, that you may prepare yourselves to do something good and useful when you are old enough to go out into the world and take care of yourselves. I am glad that you have set before you high ideals. You learn to write well only by imitating as closely as you can some superior penman. So in life, the higher you place your aims, the more likely you will be to make your lives somewhat near them. But from what I heard, I am afraid you look at the matter in too dreamy a way. By-and-by is a beautifully indefinite time for us to put into effect, our good resolutions. It costs no effort to be self-sacrificing, industrious, or, good, there. The most indolent person is willing to work hard by-and-by, and nobody ever intends to be selfish or wicked then.

"But, boys, if you go on dreaming your dreams, and laying your plans for some indefinite future time, and never commence to prepare for the accomplishment of them, it would be better for you never to waste your time over such day-dreams. You can be, in a great measure, what you wish to be, but only by constant, untiring. effort. And you must begin now. It takes a lifetime to build a character. You are laying the foundation in your schooldays. If you spend the first eighteen or twenty years of your lives heedlessly, indolently, forming bad habits, you will find it almost impossible by-and-by to change to earnest, upright men.

Life is short enough at the longest. If we intend to do anything great or good, we must be about it at once. I would like to see Will rich, that he might 'do good with his money; Ned a scholar, that he might exert a wide influence for the right; and I would like, oh, so much, to have Jo consecrate himself to the Saviour, that his life might be a rich harvest in winning souls for the Master; but boys, as you wish to make real the ideal pictures of this pleasant afternoon, I implore you to begin now to cultivate these noble, manly, Christian characteristics which you admire."

The teacher sat down. The boys and girls remained almost spellbound by her earnest manner and words. Will studied a crack in the floor; Ned watched the teacher's face with a new light on his own, while JO gazed vacantly out through the open window, though the fields and distant hills were dimmed in his vision by other pictures crowding into his mind. A woodpecker tapped on an old tree by the door, a robin chirruped a few notes in the branches above.

Many years have gone by since that afternoon at the old country school-house, but whenever I hear boys and girls planning for the future, the words of that faithful teacher come back to me; and I have written them for those who are promising themselves to do better by-and-by.

Little Star.