ABOUT DR. LIVINGSTON.

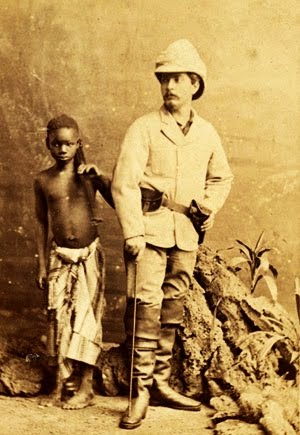

ALL of the readers have heard of Dr. Livingston, the great African explorer, how he went into the heart of Africa, miles and miles beyond any place where white men had ever been, and how he laid down his life for his great undertaking. You have heard how fond the natives were of him, and how they staid by him to the very last. You may like to hear just how it was that he gave up his life in that far-off land.

I suppose you all know that Dr. Livingston died on Mayday morning, 1873. He had been very ill since October. He marched slowly, on account of sickness. The swollen rivers and marshy ground hindered him. At Christmas he came to the River Chambeze, and offered this thanksgiving:

"I thank the good Lord for the good gift of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord."

As they went on, the weather grew worse. The country was so flooded that they could only distinguish the rivers from their banks by the currents. There were long stretches of grass and sponge, with great elephant holes. Besides all this, they were very hungry, for the natives refused them food. Once a mass of furious ants attacked Dr. Livingston in the night, driving him out of the hut. Notwithstanding all these trials, he wrote on his last birthday, March 19,1873, "Thanks to the Almighty Preserver of men for sparing me thus far on the journey of life. Can I hope for ultimate success? So many obstacles have arisen! Let not Satan prevail over me, O my good Lord Jesus!"

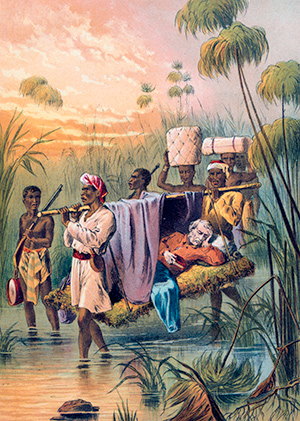

On the 21st of April he was much worse. He tried to ride, but could not sit up; so Chumah and Susi, his faithful attendants, made a palanquin, which they called a "kitanda," to carry him on. April 29 was the last day he traveled. He told Susi that morning to take down the side of the hut to bring in the kitanda, because he was too weak to walk out to it, and the door was too narrow to admit it.

That day they crossed a river, then a swamp; and, when they came to a dry plain, he would beg them to lay him down. At last they reached Chitambo's village, in Ilala, and laid him under the eaves of a house in a drizzling rain, till they could build a hut for him. The next day he did not try to move. He asked a few questions concerning the country, especially about the Luapula.

His servants knew the end was not far off.

About four o'clock that night, the boy who lay at his door called to Susi that their master was dead.

The candle was burning, and they saw him kneeling at the bedside. He had died while at prayer, on his knees, in the attitude he always wished to take when praying to God.

He had found that the usual way of conducting the Episcopal service, by the reading of prayers, did not give ignorant people any idea of a Supreme Being; so he always kneeled, and prayed with his eyes shut. Always in his travels he aimed at two things, to teach some of the truths of Christianity, and to rouse the natives to feel the awful guilt of the slave trade.

The curiosity of the people was very great. "Do people die with you?"

asked two intelligent young men. "Have you no charm against death?" "Where do people go after death?" Dr. Livingston told them of the Father, and that he hears the prayers of his children; and they thought this was natural.

After the death of Dr. Livingston, his faithful servants, Susi and Chumah, embalmed the body, and carried it to the coast. It took nine long months, and they encountered innumerable difficulties; but they persevered, and the remains now lie in Westminster Abbey.