JEREMIAH AND THE REMNANT IN

JUDEA.

A MONTH had passed since the capture of Jerusalem. Nebuchadnezzar was waiting at Riblah for news of the success of other military enterprises, which he was conducting at the same time.

But on the 10th of August the suspense at Jerusalem was broken by the appearance of Nebuzaradan, the captain of Nebuchadnezzar's bodyguard. He was accompanied by a detachment of the Chaldean army, and brought orders to put the finishing stroke to the work of destruction.

The temple was committed to the flames; the palace and the houses of the nobility shared its fate; the walls of the city were thrown to the ground. The envious heathen from Moab and from Ammon gloated over the spectacle of Zion's humiliation, and clapped their hands in glee. Edom, especially, the old enemy of Jacob's race, stood by and exultingly cheered on the work, crying out, "Rase it, rase it, even to the foundations!" The golden, the silver, and the brazen vessels of the temple were carried away to grace the idolatrous festivals of the Chaldean conqueror. The great brazen sea, or laver, and the lofty and richly-ornamented pillars of brass standing in the temple porch, named Jachin and Boaz, relics of the times of Solomon, which had passed unharmed through all the earlier spoliations of the temple, were now seized, broken to pieces, and carried away to Babylon.

Along with this treasure, the Chaldeans carried off great numbers of the people, especially those of the better class, until the city was almost depopulated. Only the poor of the land were left to look after the vines and other crops. Seventy-one prominent exiles, including the chief and the second priests, three of the guardians of the temple, the chief military officer of Jerusalem, five members of the royal council, the keeper of the army register, were carried to the king of Babylon at Riblah, and slain before his eyes. The first of this devoted list, Seraiah, the chief priest, was the father of Ezra the scribe.

Over this scene of devastation and woe, Jeremiah uttered those pathetic lamentations, which cannot even now be read without profound emotion.

They are not unmeaning outbursts of passion; their great, deep tide of feeling rolls along the channels of genuine poetry. They appeal alike to the tastes and to the sympathies of the reader.

The weeping prophet, who had long foreseen and given warning of the coming ruin, and who had offended the Jewish king and court by the directness and urgency of his speech, had been thrown into prison, and lay in chains when the city was taken. But by some means Nebuchadnezzar became acquainted with the character of Jeremiah, and felt a reverence for his prophetic office, mingled, possibly, with superstition. At all events, when the captain of the guard was sent to complete the destruction of the city, he received a special commission to look well to Jeremiah, and not only to do him no harm, but to follow his wishes to the letter.

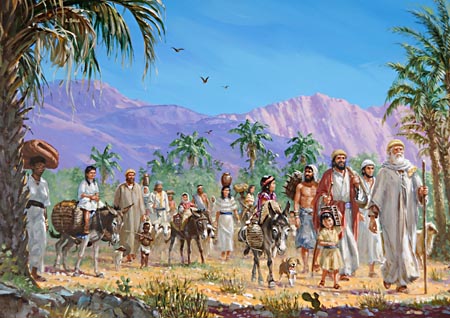

So, one of the first acts of the Chaldeans was to penetrate to the court of the prison where Jeremiah was confined, to take off his chains and set him free. Gathering together the exiles, they took Jeremiah with the crowd on the northern road toward the fatal city of Riblah. However, when they reached Ramah, six miles from Jerusalem, Nebuzaradan, captain of the guard, drew the prophet aside, and informed him that he was free to go where he wished. Should he choose to come to Babylon, the captain promised to look well to his interest, but if he preferred to remain, the whole land was before him to go whithersoever he pleased.

Thus a brilliant prospect seemed open to the long-persecuted and afflicted Jeremiah. The liberated prisoner might hope to perform a splendid part in exile, like that of Daniel.

Wealth and honor were almost within his grasp; but with a truly loyal heart he sacrificed all these prospects and remained, with hope, of doing something for his prostrate country. "He refused," says Josephus, "to go to any other spot in the world, and he gladly clung to the ruins of his country, and to the hope of living out the rest of his life with its surviving relics."

Evidently the first thing demanded by patriotic feeling was to rally once more the brokenhearted remnants of the people around some common center, and to keep alive by all possible means the peculiar spirit of the Jewish religion and the hope of the coming Messiah. The people must not be suffered to lose faith in themselves as the chosen people of God, through whom all the nations of the earth should be blessed. Of all persons remaining in the Holy Land, Jeremiah, the inspired prophet, was best fitted to lead in this work.

Nebuchadnezzar appointed Gedaliah civil governor over the desolated country. His father, Ahikam, had been a firm friend of Jeremiah, and he inherited his father's regard for the prophet His grandfather, Shaphan, had been the royal secretary under King Josiah. Jeremiah, upon being released, attached himself to Gedaliah, who had established the new capital at Mizpah, an eminence within sight of Jerusalem, four and a half miles to the north. Here were gathered such persons of eminence as had escaped death or deportation, among them the daughters of the exiled king, Zedekiah.

Thus a degree of importance was not wanting to the nucleus now gathered around Mizpeh. The place itself was distinguished as an outpost of the defenses of Jerusalem toward the north, which had been originally fortified by King Asa. A high enclosed courtyard containing a deep well furnished secure quarters for the garrison. Here Gedaliah took up his residence. Hither, from their various hiding-places in the open country, the scattered soldiers and officers soon began to gather, with Johanan, son of Kareah, at their head. Hither flocked the fugitive Jews from beyond Jordan—from Moab, from Ammon, and even from hostile Edom. Gedaliah received them with a generous cordiality, gave them his oath that if they would submit to the king of Babylon they would be unmolested, and encouraged them to gather in the waiting harvests of summer fruits, of wine and of oil. He also advised them to return and to occupy their towns and cities as of old.

From, Exile to Overthrow.