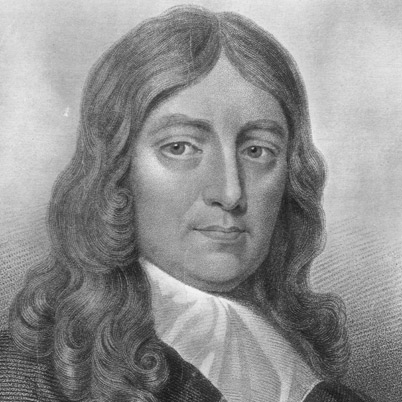

JOHN MILTON.

NEARLY three centuries ago, in a comfortable dwelling in one of the suburbs of London, was born that great master of epic poetry, John Milton, so well known as the author of "Paradise Lost." The din of the great city into which he came was in striking contrast to the quiet reserve of the life, which followed.

The parents of Milton were people of some culture. The father, a student of Christ College, was noted for being a firm believer in the Protestant faith, which was then very unpopular in England.

For this cause, he was disinherited by his family; but although he was now obliged to make his fortune by his own energies, he was still, in the intervals of his business, a busy student, being unwilling, as he said, to give up his liberal and intelligent tastes "to the extent of becoming altogether a slave to the world." He also wrote verses, and was an excellent musician. His wife was a most exemplary woman, well known through all the neighborhood for her benevolence. Thus we see that in his childhood and youth Milton had every encouragement toward the high and refined tastes, for which he was so remarkable, even when a child.

He partook largely of the noble spirit of his parents, and through all his life remained an unbending advocate for freedom. His childhood is said to be well described in one of his poems:—

"When I was yet a child, no childish play

To me was pleasing; all my mind was set

Serious to learn and know, and thence to do,•

What might be public good; myself I thought

Born to that end,—born to promote all truth,

All righteous things."

His father spared no pains in his education. He was a diligent student, and it is related that before the age of ten he had a very learned teacher, "a Puritan, who cut his hair short;" and at twelve, in spite of weak eyes and severe headaches, he often studied till midnight. After a time he was sent to Christ College, Cambridge, where he made rapid progress in his studies, especially in the classics. While here, he wrote his celebrated hymn, "The Nativity."

In 1632 he left school, having taken his degree M. A., and went to the village of Horton, which was now his father's home. In the accompanying picture may be seen the old church at this place, which is still standing. Here he remained several years, improving his time in study, and in writing several poems, the best known being "Comus."

In 1638 he left his father's home, and made a tour through Italy and France, where he was received with considerable honor. He returned home when England was distracted by political strife and religious dissension, and engaged actively in public affairs till the Restoration. His close application to study and much use of "midnight oil" had severely taxed his eyesight, and near the close of the year 1652, his light went out in utter darkness,—Milton was hopelessly blind. Yet with a fixed resolution and a will undaunted, he continued to study and write till the close of his life.

Says an eminent writer, in speaking of his habits and personal appearance, "He studied till midday; then, after an hour's exercise, he played the organ or the bass violin. Then he resumed his studies till six, and in the evening enjoyed the society of his friends. When any one came to visit him, he was usually found in a room hung with old green hangings, seated in an arm-chair, neatly dressed in black; his complexion was pale; his hair, of a light brown, was parted in the midst and fell in long curls; his eyes, gray and clear, showed no signs of blindness. He had been very beautiful in his youth, and his English cheeks, once delicate as a young girl's, retained their color almost to the end. His face, we are told, was pleasing; and his straight and manly gait bore witness to his intrepidity and courage. Something great and proud breathes out yet from all his portraits; and certainly few men have done so much honor to their kind."

It was during this period, when persecuted on account of his bold defense of liberty, and deserted by his friends, his home cheerless on account of domestic troubles, that he could see with his inner sight what his mortal eyes had failed to behold,—those glorious visions of a lost world redeemed by

the sacrifice of One Infinite. The outgrowth of these high conceptions was "Paradise Lost," which

is perhaps the most widely known of all Milton's works. It is related that Milton showed this poem to a friend, who, upon reading it, said, "Thou hast said much of paradise lost; what hast thou to say of paradise found?" whereupon Milton replied nothing, but fell to musing, and as a result, produced a sequel poem, "Paradise Regained."

His life was simple and majestic, his writings approaching the sublime. He stands out alone in the corrupt age in which he lived, the next greatest poet of his time,—a man seeking after simplicity, purity, and holiness.

His remains lie in the churchyard at St. Giles, where a small monument marks his last resting place.

W. E. L.