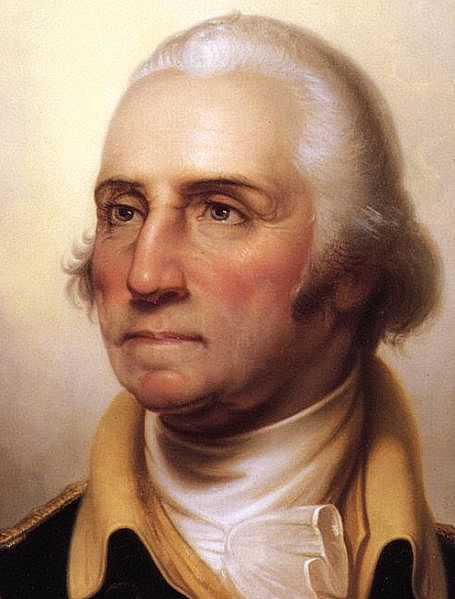

OUR HERO.

PERHAPS there is not a boy in the United States who has not heard the story of that other boy who lived more than a hundred years ago, the one, I mean, who owned a little hatchet and went here and there trying its bright, keen blade on everything he met, and then said those words that will never be forgotten, "I cannot tell a lie."

Not every one, though, knows the other good and pleasant things that are told of the great General Washington when he was young. He was, true, brave, and noble, and was a leader and ruler even then. When the other boys had disputes or quarrels, they always called upon George Washington to settle them, as if what he said must be the right thing.

The miserable, sneaking boys, who thought it good fun to torture a kitten, or tease a little girl; or hoot at a beggar, did not like to be caught at it by this noble-minded schoolmate, who scorned to be guilty of anything so small.

He was fond of fun, though—real, pure fun. No shout or laugh was merrier than his on the playground. One of his favorite amusements was to arrange his playmates in companies, pretending that they were soldiers and he was their leader,

marching and counter-marching them, the whole ending up in a great battle, of course always coming off victorious, and so these play battles were pictures of what was really to happen in the years that lay before him.

This boy, whose laugh was the merriest, who could out-wrestle and rout-run his mates, carried his whole soul into the schoolroom as well. Perhaps this was one reason of his after greatness; he could not be halfhearted in anything he undertook.

"This one thing I do," seemed' to be his motto during school hours.

And it brought its reward, too, as faithful study is always sure to do; for he always thoroughly mastered his lessons.

He had great taste for mathematics, and was soon beyond simple arithmetic, studying geometry, trigonometry, and surveying. He spent much of his time surveying the lots around the school-house.

He used to make little books of foolscap paper, and copy different things into them. Among them were copies of forms used by men in transacting business,—bonds, notes, etc. Extracts from poems he wrote here, too; but the most remarkable for a boy to copy were some rules of conduct. Here are some of them-

"Gaze not on the marks and blemishes of another, and ask not how they came.

"What you may speak in secret to your friend, deliver not before others.

"Let your recreations be manful, not sinful.

"When you speak of God, or his attributes, let it be seriously and in reverence.

"Honor and obey your parents, although they be poor.

"Labor to keep alive in your heart that little spark of celestial fire called conscience."

Are they deep? Study them. The one who copied them was only thirteen at the time, The years that followed proved, though, that he must have squared his life by them. Not only did he keep the' "little spark" alive, but it shone, it blazed. The love, obedience, and honor he gave his mother, was something wonderful. When he was made president, he went to bid his aged mother good-by. The thought that he might never see her again made him very sad, and the grand general leaned his head on his mother's shoulder and wept.

"Go, my son," she said, "and may Heaven and your mother's blessing be with you always." It was not strange that a boy like himself should become a man that a nation loved and honored, and that when he went to take his place in the presidential chair, the whole country with one voice shouted, "Long live Washington!" nor that they poured out from mountains and valleys to welcome their hero as he passed along, strewing flowers before him and singing,-

"Strew your hero's way with flowers!'

Marcia McDonald.