THE CHINESE CAPITAL.

ON a small tributary of the River Pei-ho, in the province of Chili, stands one of the oldest cities of the Chinese empire, Peking.

It is about forty miles south of the great wall, built long, long years ago as a barrier between the Chinese and the fierce Tartar tribes to the north. This city, the capital of the province of Chili and also of the empire, has a population of nearly two millions.

There are two parts to the City; the southern, the Chinese city, is the larger, and contains fifteen square miles; the northern, the Tartar city, contains twelve square miles. These cities are each surrounded by a wall thirty feet high, twenty-five feet thick at the base, and twelve feet at the top.

The walls are built of earth or rubbish, and faced with brick laid nearly smooth and perpendicular on the outside, but on the inside receding in the form of steps, while at intervals are sloping banks of earth that enable a horseman to gain the top of the wall.

The Chinese city has the greater number of inhabitants. It is not nearly so well built nor so clean as the Tartar city. In fact, cleanliness does not seem to be numbered among the virtues of a well-bred Chinaman; and the stench arising from the filth and garbage of the streets would be very offensive to any but a native. The principal streets are one hundred feet broad, and extend from one side of the city to the other, with a gate at each end. Branching off from these main thorough-fares are irregular streets, mere alleys or lanes.

The houses on these back streets are poor, squalid affairs; on the principal streets, however, they are of brick, well built, and often highly ornamented with gilding.

Along the main streets are ranged the shops, with tall signposts at each side of the building, setting forth the superiority of the goods, and the fair dealing of the merchant. The shops are open, and the goods are heaped confusedly together in front. In the daytime, all is hurry and bustle; but as night comes on, quietness settles down over the city, broken only by the watchmen, who pace the dimly lighted streets, and mark the time by striking two pieces of bamboo together.

Three gates lead from one city to the other. The Tartar city consists of three enclosures, one within another, each surrounded by a wall nearly as solid as the outside city wall. This is called the prohibited city. Here the queen rules the harem in the "palace of earth's repose," the office-seekers are presented to the emperor in the "tranquil palace," and at another place stands the "gate of extensive peace," a balcony, where the emperor receives his courtiers. There are beautiful gardens, with artificial lakes, fountains, groves, and temples. On the west side stand some public buildings and a printing office. Peking publishes a daily journal of sixty or seventy pages, called the Peking Gazette.

It contains an account of all the principal events of the kingdom, together with all the petitions presented to the emperor and his answers to them. It publishes an account of all the judicial affairs, which the editors cannot change in the least, without rendering themselves liable to be put to death; and knowing that such things have been done in times past, the editors are very careful to make no changes. Over each of the four gates and in each corner of the yard stand towers, where the troops and guard are stationed.

The second enclosure, called the imperial city, is oblong in shape, and is surrounded by a wall six miles in circumference.

No one is allowed to go within these walls except by special permission, and then only on foot. Here stand the dwellings of the officers, numerous temples, and several official buildings. On the north side is an artificial mountain, one hundred and fifty feet high; and on the west, a large park, with an artificial lake more than a mile long.

The third enclosure is the Tartar city proper. It contains the principal government offices, the medical college, the national academy, and other prominent buildings, besides several churches.

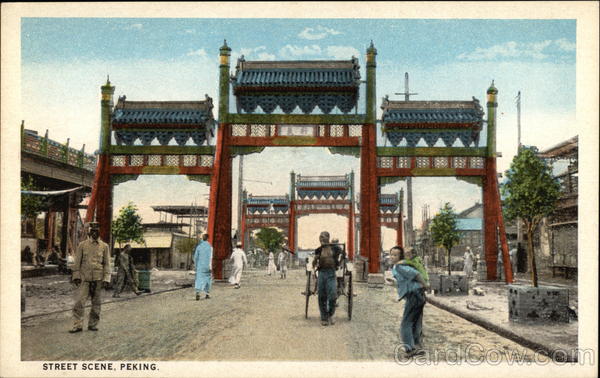

Once outside one of the thirteen city gates, one of which, is shown in the picture, nothing can be seen but a long stretch of wall, with watch-towers projecting out some fifty feet, and the tops of pagodas, and the flag-staffs in front of the officers' houses.

In the well-cultivated suburbs stand many fine dwellings, together with little hamlets surrounded by trees, so that from a distance Peking looks as if it stood in the midst of a vast forest.

The country becomes hilly about eight miles northwest of the city, and has been converted into a park containing nearly twelve square miles. The Chinese are said to be among the best landscape gardeners in the world, and here they have had a fine chance to display their skill. The hills and vales are interspersed with lakes, rivulets, and canals, with here and there a tangled thicket, through which a path leads to some secluded summer-house, or a highly cultivated piece of ground, with a palace for the emperor or his ministers standing in the midst of it. These beautiful houses were plundered by the French and English soldiers in 1860 on their way to capture the capital.

The winters in Peking are cold, the thermometer ranging from ten to twenty-five degrees above zero; in the summer it, stands from seventy-five to ninety. The climate is said to be healthful. Violent storms are of frequent occurrence, and in 1671 an earthquake destroyed the city, and four hundred thousand of the inhabitants were buried in its ruins.

The Chinese were formerly very careful to exclude all foreigners from their country, and no ships were allowed to land at any of their ports.

From time to time embassies were sent from different nations to Peking to treat with the government relative to opening up communications with other countries, but each time they failed to accomplish their object.

After many years the Chinese have finally consented to let foreigners trade at their ports; they allow travelers to visit China, and their own inhabitants to live in other lands. Christian missionaries have opened up missions in many parts of the country, and are doing a good work in bringing the light of the gospel into this heathen land.

W. E. L.