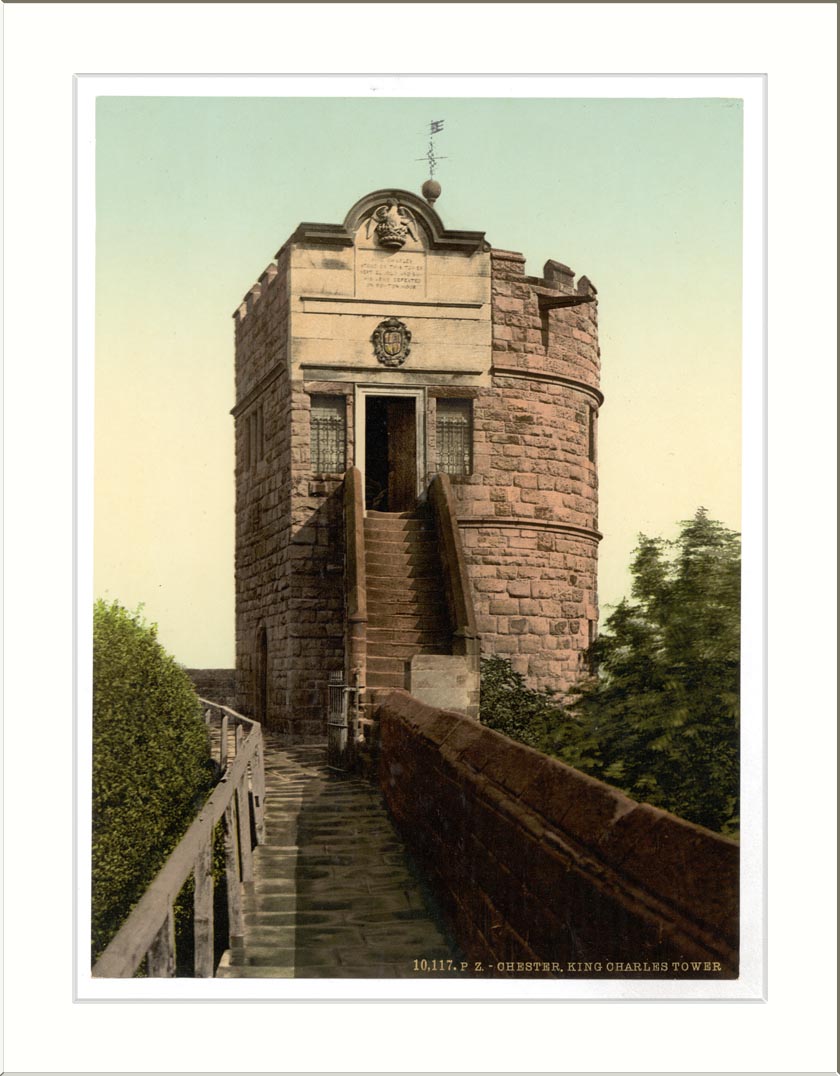

KING CHARLES'S TOWER.

CHESTER is one of the oldest cities of England. It is situated on the River Dee, near where it flows into the Irish Sea, about one hundred sixty miles northwest of London. Built on a high rocky elevation, it is still surrounded by massive walls, erected many hundred years ago. On these walls were built, at regular intervals, round towers, which were once used as watchtowers. The picture shows one of these towers, which bears the name of King Charles I. How it came to be so called may be learned by the following story:— King Charles reigned over England during the first part of the seventeenth century. Those were very troublous times in England, for the people were becoming tired of having their kings take so much power to themselves and not allow their subjects to have anything to say about the government. But Charles only went right on doing just as the kings had done before him. If he wished to undertake any war, he would do so of his own accord, and then make the people pay the expenses of it. And if any of his subjects displeased him, he would imprison them, or put them to death without allowing them a trial. The people at last became so angry at these and other acts of tyranny that many of them joined an invading army from Scotland, and determined to make the king come to terms. Most of the nobles stood by the king, and raised an army to defend him, and so a civil war began. The king was soon obliged to leave London and seek refuge in such towns as were friendly to his cause. Among these was the city of Chester, and from the tower shown in the picture the king witnessed the defeat of his forces in the plains below. The tower has a lower and an upper room.

In the latter the king held a council just before the battle, and so it is still called the Council Chamber. The people of Chester thought so much of their king that they withstood the seige of his enemies until they were so much reduced as to feed on horses, dogs, and cats.

At last the king was so badly beaten that he surrendered himself to the Scots in the hope of securing their favor. But they turned him over to the English, who were by this time so angry at him that though foreign countries, his son, and many of his own countrymen interceded for his life, he was condemned to death and was executed on the scaffold.

With all his faults, King Charles had many good qualities, and was partly excusable for his course in that he only claimed the privileges that his fathers had exercised before him; and Christian charity cannot but condemn the people who went so far as to take his life.

C. H. G.