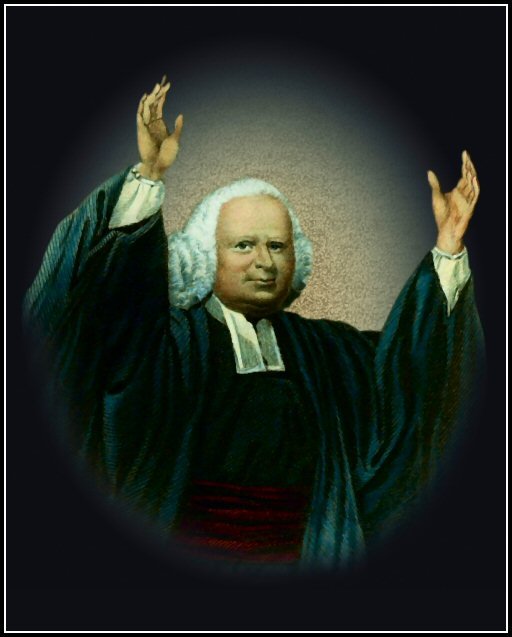

GEORGE WHITEFIELD.

IN the southern part of England, in the beautiful valley of the Severn, and on the banks of that noble stream, lies the ancient city of Gloucester, with its regular streets, its majestic cathedral and other relics of 'by-gone days. There are in this city three places, which the traveler visits with special interest. One is the old church of Mary de Crypt, where lie the ashes of Robert Raikes, the founder of Sunday-schools; another is the little enclosure, which marks the spot where the good Bishop Hooper was burned to death in the reign of the Bloody Queen Mary. The third, and to us just now the most interesting, is the Bell Inn, in which was born one of the greatest reformers that England ever gave to the world.

George Whitefield, the sixth son of Thomas and Elizabeth Whitefield, was born Dec. 16, 1714.

His father died when he was but two years old, and George was ever afterward his mother's favorite child. The fact that he was born in an inn, like the Saviour of the world, seems to have made quite an impression on the boy's mind. When a mere child, he used to tell his mother that he wanted to be a minister when he was grown, because, having been born in an inn, he ought to be better than other men.

As the boy grew older, he was very anxious to learn, but as his mother was poor, he seemed likely to have no advantages except the schools of his native town. At the age of fifteen he left school and assisted his mother in the inn for two or three years. Finally, through the influence of some of his mother's friends, he obtained a situation at the University of Oxford where he could partly earn his own way. This was when he was in his eighteenth year. While at Oxford, Whitefield became acquainted with John and Charles Wesley, who were the leaders of a class of young men in the University who "lived by rule and method," and were: therefore called Methodists.

Whitefield soon became one of the little company; and from this time on, he began to have a remarkable religious experience.

He now fully decided to devote his life to the ministry; and every hour was studiously given to

preparation for the great work to which he had solemnly dedicated himself. Says his biographer:

"He visited' the prisoners in the jails, and the poor in-their cottages, and gave as much time as

he could to communion with God in his closet."

Whitefield was ordained to the ministry before he had completed his twenty-first year. He was anxious to spend more time at the University, and felt that he was not yet prepared to enter upon so important a work; but Bishop Benson and others in authority were so impressed with his piety and earnestness that they almost insisted upon his taking orders. He preached his first sermon in the church of Mary de Crypt, in his native town. Of this sermon, he himself says: "As I proceeded, I perceived the fire kindled, till at last, though so young, and amidst a crowd of those who knew me in my childhood days, I trust I was enabled to speak with some degree of gospel authority. Some few mocked, but most, for the present, seemed struck; and I have since heard that a complaint was made to the bishop, that I drove fifteen people mad the first sermon. The worthy prelate, as I am informed, wished their madness might not be forgotten before the next Sabbath."

Perhaps no man since the days of the apostles has so completely devoted himself to the work of preaching the "gospel as it is in Jesus" to all classes of men, rich and poor, high and low, as did George Whitefield. He took for his motto:

"This one thing I do;"

and his life fulfilled these words. He was accustomed during the greater part of his ministry to speak to the people as many as forty hours in a week, and sometimes more. Outside the pulpit his labors in conversing and praying with his converts were almost incessant. During one week while in London, he is said to have received one thousand letters of inquiry from those, who wished to be saved. Shortly after he entered the ministry, he was invited to go to London, where he preached in some of the first churches in the city as well as to the prisoners in the jails, and in the open air to the poor people who gathered to hear him on the commons. He gained many warm friends among all classes.

He traveled throughout England, Wales, and Scotland, his earnestness and eloquence everywhere bringing him great crowds.

Says he, in speaking of his labors at one place:

"It was wonderful to see how the people hung upon the rails of the organ-loft, climbed upon the leads of the church, and made the church itself so hot with their breath, that the steam would fall from the pillars like drops of rain. Sometimes almost as many would go away for want of room as came in, and it was with difficulty I got into the desk to read prayers or preach. Persons of all ranks not only publicly attended my ministry, but gave me private invitations to their houses."

He was frequently obliged to preach in the open air on the moors and commons, where as many as twenty thousand people often gathered to hear him. These were solemn seasons to him, as his own words testify:" The open firmament above; the prospect of the adjacent fields; with the sight of thousands and thousands, some in coaches, some on horseback, and some in the trees, and all so affected as to be moved to tears together, to which sometimes was added the solemnity of the approaching night, were almost too much for me; I was occasionally all but overcome."

Mr. Whitefield's labors were not confined to England. He came to America seven times, where he assisted the Wesleys in their missionary labors in Georgia, and labored and preached extensively in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and other towns of the East. His success in this country was as great as in England, and he came to be greatly loved and venerated by all good people.

He established an orphan-school at Savannah, Georgia, where children, black as well as white, found a home. He brought over from time to time quite large companies of homeless children from London to his Bethesda, as he named it.

It was while on his seventh visit to this country that he was called to lay down his armor, and go to his final rest. He preached and labored to the very last, and only went to his room a few hours before his death. His health had been failing for some time, but he could not bring himself to give up, and take needed rest. The day before his death he said, "I am weary in the work but not of it." He died at the house of Mr. Parsons, first pastor of what is now, known as the Old South Church, in Newburyport, Mass. At his own request, he was buried in the vault beneath Mr. Parsons's pulpit, where his bones still rest. One who attended service in this church during the past summer, writes in a letter:" After the sermon, the sexton took us down into the vault under the pulpit, and there we saw all that is left of George Whitefield. To think that that is all that remains of that great man, and that those bones and that little heap of dust was once a warm, living human being, that thought, and moved, and spoke, and loved just as fondly as we do! And he walked those very aisles, and spoke his wonderful words from that very pulpit! There are two other coffins in there. They contain the remains of Mr. Parsons and Mr. Murray, the first two pastors of the church. Whitefield's monument stands in the corner of the church, where everybody can see it."

It must not be thought that this good man had no trials and persecutions in his long and successful ministry. His zeal in defending truth and pointing out wrong made him many enemies, and his experience was such as to well give him a place among the great reformers of the world.

E. B. G.