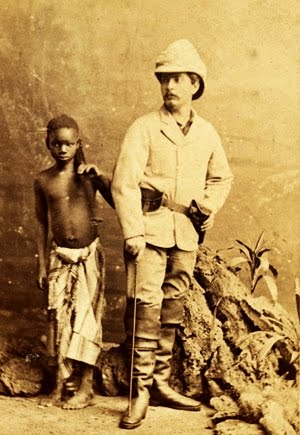

DAVID LIVINGSTONE.

MANY of you are undoubtedly familiar with the name of that great African explorer, David Livingstone, and perhaps you remember reading in an INSTRUCTOR printed a year or two ago, of his last days in the Dark Continent, and of his death there. Possibly you would like to hear about his early life at home, and the causes that led him to engage in such a difficult and self-sacrificing work.

David Livingstone was born the 19th of March, 1813, at Blantyre, Scotland, and was the second child in a family of five,—three boys and two girls. His parents were poor, but of sterling worth. His father was an earnest and resolute Christian, and possessed in no small degree the missionary spirit. He was a tea-peddler; and while traveling through the neighboring parishes, selling his goods, he distributed large quantities of tracts, and talked to the young on the subject of religion. When he was quite advanced in years, and it was difficult for him to study, he set himself to master the Gaelic language, that he might be able to read the Bible to his aged mother, who understood that tongue the best. Mrs. Livingstone was a delicate little woman, active, orderly, and scrupulously neat; and she trained her children to the same virtues. She was sunny and good natured, and made the home-life bright.

The parents required of the children implicit obedience and much self-denial. It is said that when David was a very little boy, he returned home one evening later than usual, and found the door barred against him; for it was one of his father's rules that the doors should be bolted at dusk, and every child was expected to be in. David had no idea that a rule would be broken to favor him, and so, having obtained a piece of bread, he sat down on the door-step, intending to stay there all night; but his mother saw him, and let him in.

He learned, under such training, to make the best of things, and grew up a thorough-going, self-reliant young man.

When he was but ten years old, he was set to work as a "piecer" in a cotton-mill. It was weary work for one so young, but he felt amply repaid, when, at the end of his week's work, he placed his first earnings, sixty cents, in his mother's lap. She gave him back enough to buy a Latin grammar, and for several years he studied Latin in an evening school from eight till ten o'clock. In his Journal he says, "The dictionary part of my labors was followed up till twelve o'clock, or later, if my mother did not interfere by jumping up and snatching the books out of my hands. I had to be back in the factory by six in the morning, and continue my work, with intervals for breakfast and dinner, till eight o'clock at night. I read in this way many of the classical authors."

He read everything he could get hold of except novels, and he was not afraid of hard study. He was passionately fond of natural history, botany, and geology, and with his brother, used to spend what few holidays they had in scouring the neighboring fields for specimens.

When he was nineteen, he was set at spinning. He was very glad of the change, not only because he had higher wages, but because he had more time for reading. He had no more spare time than before, for his working hours were still from six in the morning till eight at night; but he could fasten his book up on the frame before him, and as he passed and re-passed it at his work, catch a sentence now and then, and in this way slowly read a book through.

About this time he read a book that led him to see the wonderful love of Christ in coming to die for us; and he was so glad and thankful that he resolved to give all his earnings, except what he needed to live on, to the cause of missions. By and by an appeal was made by a missionary to China, showing the great amount of work to be done among the heathen, and the scarcity of help, and pleading for faithful and earnest Christians to enter that field of labor. Then it occurred to Livingstone that the best service he could render to God was to give himself wholly to the missionary cause. He consulted his parents and the pastor, and finding that they approved of his plan, he set himself steadily at work to prepare for his mission. He made the meager earnings of six months serve not only to support himself while he was at work, but also to cover his expenses while attending school in the winter.

He intended to go as a missionary physician, and to do this he had to go through a costly medical course; but he had determined to receive help from no one. He went first to Glasgow, and afterwards to London.

He wished to make China his field of labor; but as the ports were then closed on account of the opium war, he turned his face towards Africa. He stopped first at Kuruman, the most Northern mission-post of the Dark Continent. Becoming convinced that the missionaries were stationed too closely together to accomplish all the good that might be effected, he wrote home to the Missionary Society that sent him, to gain permission to go farther up into the interior, where no white man had ever gone. While waiting for the desired permission, he made long journeys into the surrounding country, acquainting himself with the habits of the natives, and learning their language.

At last the consent of the Society was obtained, and Livingstone, with his wife, the daughter of a missionary in Kuruman, started out to give to the natives of the interior a knowledge of the true God. They went north of Kuruman, and planted a very successful mission, training the natives so that they might teach their countrymen themselves. But the Doctor's plan was not to spend his time solely in teaching the people about Christ; he meant to prepare the way for others to follow him into the heart of Africa, and finish up the work that he had only time to begin. To do this, he tried to find out if there was not a waterway from the interior to the sea, that by a more direct route and at less expense the gospel might be brought to the inland tribes. So, leaving his missions to the care of the trained natives, he forced his way to the west coast, over a route never before traveled by white man or native. The obstacles he had to meet were almost insurmountable; yet with the same perseverance that characterized him when a boy, he kept steadily to his purpose. He did not find the waterway that he expected to discover, but he accomplished many other things.

On his return, he made a similar journey to the east coast, and with very much the same results. He often met with bitter disappointment, and his work was seriously hindered, because his own people did not have faith in his plans, but thought that he was spending the money given him to use in the missionary cause, to forward his own selfish ends. Yet he was cheerful in face of all this discouragement, never once losing faith in the Guiding Hand.

There is not space to tell you of his return to England, and his two other journeys to Africa; nor how, as he had almost succeeded in his life work, his light went out in his little canvas tent in Ilala, and his servants found him, one morning, with clasped hands and bended knees, dead, while praying to the Almighty for the weal of Africa.

Faithful hands bore his remains over nine hundred miles to the coast, and then took them to England, where they lie buried in Westminster Abbey, with the kings and princes of the earth.

But you must get some book telling of the life of Livingstone, and read these things for yourselves. And while you study carefully the life of one who so faithfully followed Christ, in that he "pleased not himself," may you imitate his noble Christian example.

W. E. L.